Although I have to admit this site is getting known for insanely OTT statements like this, I'm going to say it anyway:

Stephen Foster was, and is, the most influential and important American songwriter in American history.

And this actually more an official consensus, rather than any personal hyperbole - everyone on the planet knows his songs. If you don't, then you're probably living in a crater in the middle of the Atlantic with your ears fused shut. Stephen Foster's melodies are familiar across the world, even if he himself is not known as the author.

Take this version of "Camptown Races", by the 2nd South Carolina String Band (a band who make some terrific covers of his songs) and tell me that you don't know this:

Stephen Foster was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1826, of Irish descent, had only a brief education, was influenced by minstrels songs, parlor songs, German classical, negro songs and in the 19th century he set out to do something utterly batshit crazy - write songs for a living.

It's hard to imagine in these days of commercial music, but in the early half of the 19th century it was not considered a viable profession to be an official songwriter. If you wrote songs, it was because you were a performer and you charge money for your performances, not the songs. And of course, the songs were not worth anything - they were merely ditties, not at all worthy of esteem or social value like classical compositions. And, unfortunately for Steve, that's pretty much how it was for him, as a man out of his time - his songs were plagiarised, since there was no concept of copyright for songs in those days and since he wasn't a performer, he died penniless and impoverished at the age of 37.

What he left behind was, to that point, the most sophisticated, unique, memorable and oft-imitated body of songs in America. His work ranged from blackface minstrel songs, to parlour songs, to love ballads, to anti-slavery laments and whatever else he felt like. The most significant innovation was probably his ability to take the previously low form of music, the minstrel or "ethiopian" song and elevate it to a new status - he attempted to, in his own words, "build up taste...among refined people by making words suitable to their taste, instead of the trashy and really offensive words which belong to some songs of that order."

One of his first big hits, published on February 25th, 1848 was "Oh! Susanna". One of the most perfect songs in the history of the world, like, ever, it was ostensibly a minstrel song, sung from the point of view of a black man, using the, *sigh*, dialect that was so popular at the time. The lyrics are partly nonsense:

I came from Alabama wid my banjo on my knee,

I'm g'wan to Louisiana, my true love for to see

It raind all night the day I left, the weather it was dry

The sun so hot I froze to death; Susanna, don't you cry.

But they have a genuine anthemic, emotional backbone to them. The song did contain a verse that is more than a tad inflammatory in today's eyes:

I jump'd aboard the telegraph and trabbled down de ribber,

De lectrick fluid magnified, and kill'd five hundred Nigga.

De bulgine bust and de hoss ran off, I really thought I'd die;

I shut my eyes to hold my bref -- Susanna don't you cry

Accusing Stephen Foster of racism is pretty much pointless - in 1848, even "Uncle Tom's Cabin" hadn't been published yet; considering black people even human was a radical notion to some people, so to empathise and try to emulate them like Stephen Foster did probably made him quite liberal for the day. So to try and condemn him for using dated terms like "nigger" or "darkie" over 150 years ago is ridiculous. On the other hand, I do think it does undermine the emotional impact of the song for it to performed nowadays using those lyrics.

This version by the 2nd South Carolina String band is clever - it basically changes a single letter to make the word "chigger" instead, which is basically a bed-bug. It doesn't matter since its essentially nonsense, but it fits seamlessly. This version is beyond perfect in every measure:

He wrote many other minstrel songs like "Ring De Banjo", "Nelly Bly" and "Uncle Ned", but never topped "Oh! Susanna" in this area. He did also write parlor songs for the more middle-class market, like "I Dream of Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair" and "Hard Times Come Again No More" which weren't radically different from his minstrel songs beyond the fact that they weren't written in a "dialect". Here's a recording of the latter song (written in 1854) by a certain Bob Dylan fellow from 1993. Although Bob's voice was at an all time low at this point, he does actually sing the song properly, presumably because it wasn't one of his own songs:

Steve's songs were incdrebily popular with minstrel performers like Dan Emmett and E.P. Christy, but they weren't so keen on giving him the credit for the. Likewise, publishers would often publish his songs without credit. Since there was no legal defence for songwriters in those times, he basically got royally screwed over throughout his whole career.

Another interesting thing to note about Stephen Foster is that, although he wrote a lot of songs about the Southern states and was most associated with them, he only visited the South once, on a steamboat trip on his honeymoon.

Perhaps Foster's magnum opus was written in 1863, "Old Black Joe". The song combined all his previous work in the fields of minstrel songs, parlor songs and spiritual ballads. The song is a tale that was popular in the late half of the 19th century, that of the aged slave (or ex-slave) living his last days, lamenting for his long gone friends and family and his desire to join them in the after life. It's a theme that would explored again in songs like "Little Old Log Cabin In The Lane", but Steve's song is the most poignant, with the haunting chorus refrain of:

I'm coming, I'm coming, for my head is bending low

I hear their gentle voices calling Old Black Joe.

Although sung from the point of view of a black man, it's not written in a dialect, which was pretty rare for the time and paint a sympathetic but also dignified portrayal, with little of the patronisation that existed in other minstrel songs. Here's a recording from the 1930's by Cowboy group, The Sons of the Pioneers:

Still, like I said, Steve wasn't making a lot of money and on January 13th 1864 he died in a Hotel in New York, with only 35 cents in his pocket. However, his songs lasted and became renowned throughout the world. They were routinely taught in American schools, although this abated somewhat in the 1960's after the Civil Rights movement claimed that many of Stephen Fosters songs were racially insensitive. Kind of ironic, since Stephen Foster came to fame in the first place through his attempts to be sensitive to African-American culture.

Today, another re-evalutation has been going on which argues against the claim of racially insensitivity, but it's unlikely to be a debate which'll close any time soon. Partly it's probably due to the sheer influence of his songs - no-one would give a rat's ass about Will Hayes, or Henry Clay Work's racially themed material from the same era, but Steve's song are so well known that they have come to represent America's musical culture more than any other and thus attract far more debate and controversy than any other songwriter of the time.

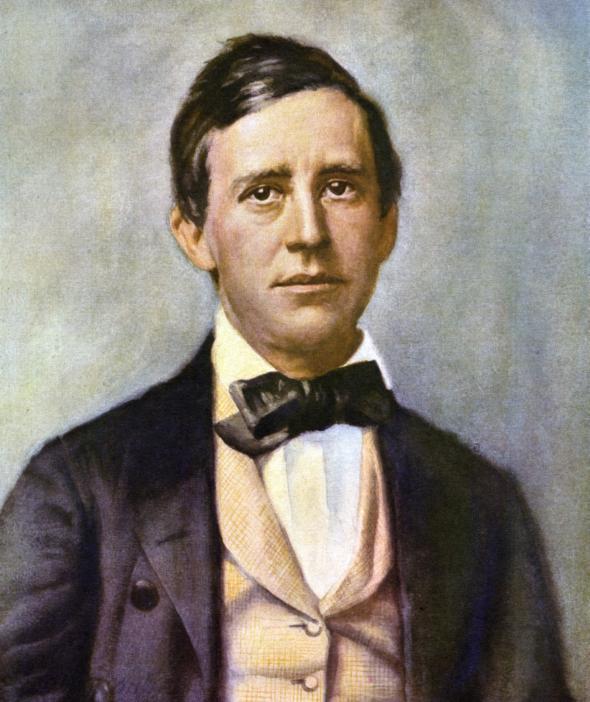

The main point about Stephen Foster is the songs themselves and they are truly beautiful - he was the first songwriter who actually saw the value in an original melody, rather than one merely stolen from a traditional song and he saw that the simple medium of the "song" could be just as relevant as any classical composition. He was a humble, shy figure from all accounts (just look at that photo at the top) and would probably never have believed his songs would cause the kerfuffle they have done over the century.

So, until I hear those gentle voices calling...

Monument to Stephen Foster, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

No comments:

Post a Comment